ANZAC Day No.1

ABOVE: When he left Brisbane along with the men of the Queensland-raised 9th Infantry Battalion aboard the “Ascanius” on 24 May 1915, the Reverend Dr Ernest Northcroft Merrington was a “Honorary Chaplain Class 1”, that is, a volunteer. Between 1 August and 18 November 1915 – when he was evacuated after contracting malaria – Padre Merrington ministered to troops in the field on the Gallipoli Peninsula, as seen in this Australian War Memorial image. Note the improvised altar made of two wooden biscuit boxes draped with Padre Merrington’s Strachítsa. This communion service was being conducted for the men of the the 3rd Light Horse Brigade at “The Apex”. Re-enlisting in the Chaplaincy Service on 29 December 1917, Padre Merrington – then attached to the 3rd Australian Auxiliary Hospital – served on the Western Front in France between 6 July and 22 November 1918. He returned to Brisbane to be discharged on 20 July 1919. His home “Northcroft” was located on Mowbray Terrace, East Brisbane. AWM Negative C2748.

Anzac Meeting.

Crowded Exhibition Hall.

Stirring Deeds Recalled.

A Solemn Incident.

ANZAC DAY ended, as it had begun, in sober recognition of the heroic deeds performed in Gallipoli at the cost of so many brave lives; deeds which are a lasting inspiration to the men now – or soon to lie – on the battlefront.

The meeting in the Exhibition Hall, which brought the first anniversary observance to a close, was an unqualified success, the big building being packed to overflowing and the speeches reaching a level of sincerity and eloquence which told how deeply ‘Anzac’ and all that it means has moved Australians.

These speeches came from his Excellency the Governor [ Sir Hamilton John Goold-Adams ], the Acting Premier, (Mr. E.G. Theodore) [ Edward Granville Theodore ], Chaplain Dr. Merrington [ Chaplain Colonel Ernest Northcroft Merrington ], Mr. J.J. Kingsbury [ John James Kingsbury ], Archbishop Duhig [ Dr James Vincent Duhig ] and Archbishop Donaldson [ St Clair George Donaldson ].

Preceding them came a short organ recital, contributed by Mr. Geo. Sampson, FRCO [ George Sampson, Fellow of The Royal College of Organists ]; who played with deep feeling, Beethoven’s “Funeral March on the Death of a Hero”, and Chopin’s exquisite “Marche funèbre”.

The Mayor (Ald. J.W. Hetherington) [ Alderman John William Hetherington ] took the chair at 8 o’clock and supporting him, in addition, to the speakers already mentioned, there were also present:

- Sir H. Rider Haggard

[ Sir Henry Rider Haggard ] - Lady Goold-Adams

[ Elsie Goold-Adams, neé Riordan ] - Hon. J. Adamson, (Minister for Railways)

[ John Adamson, State Member for Rockhampton ] - Hon. H.F. Hardacre (Minister for Education)

[ Herbert Freemont Hardacre, State Member for Leichhardt ] - Hon. W. Lennon (Minister for Agriculture)

[ William Lennon ] - Hon. J.M. Hunter (Minister for Public Lands)

[ John McEwan Hunter, State Member for Maranoa ] - Hon. W.H. Campbell, M.L.C.

[ William Henry Campbell ] - Hon. C. Holmes a’Court

[ Charles George Holmes a’Court, the-then Clerk of the Queensland Parliament ] - Bishop Le Fanu

[ Henry Frewen Le Fanu ] - Lieutenant-Colonel Moore, P.M.

[ Richard Albert Moore ] - Canon Batty

[ Francis de Witt Batty ] - Chaplain A.G. Weller

[ Alfred George Weller ] - The Reverend W. Thompson

[ The Reverend Canon Walter Thompson ] - Alderman G. Down

[ George Down ] - J. McMaster

[ John McMaster, former Mayor of Brisbane] - A.J. Raymond

[ Albert Joseph Raymond ] - H.J.C. Diddams, C.M.G.

[ Harry John Charles Diddams, former Mayor of Brisbane] - Mr. E.G.C. Scriven

[ Colonel Eric George Bennett Scriven ]

The hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee”, was a fitting prelude to the meeting.

The Mayor played only the part of chairman, and did not stand between the audience and the speakers.

His Excellency fulfilled a popular duty when he responded to the Mayor’s suggestion to read the Anzac message cabled to Australia by His Majesty the King.

The stirring words were received with a great outburst of cheering and the audience gave three rousing cheers for the King.

The subsequent speeches, all of which sounded the note of patriotism, contained more than one hint that the Anzac anniversary has come to stay.

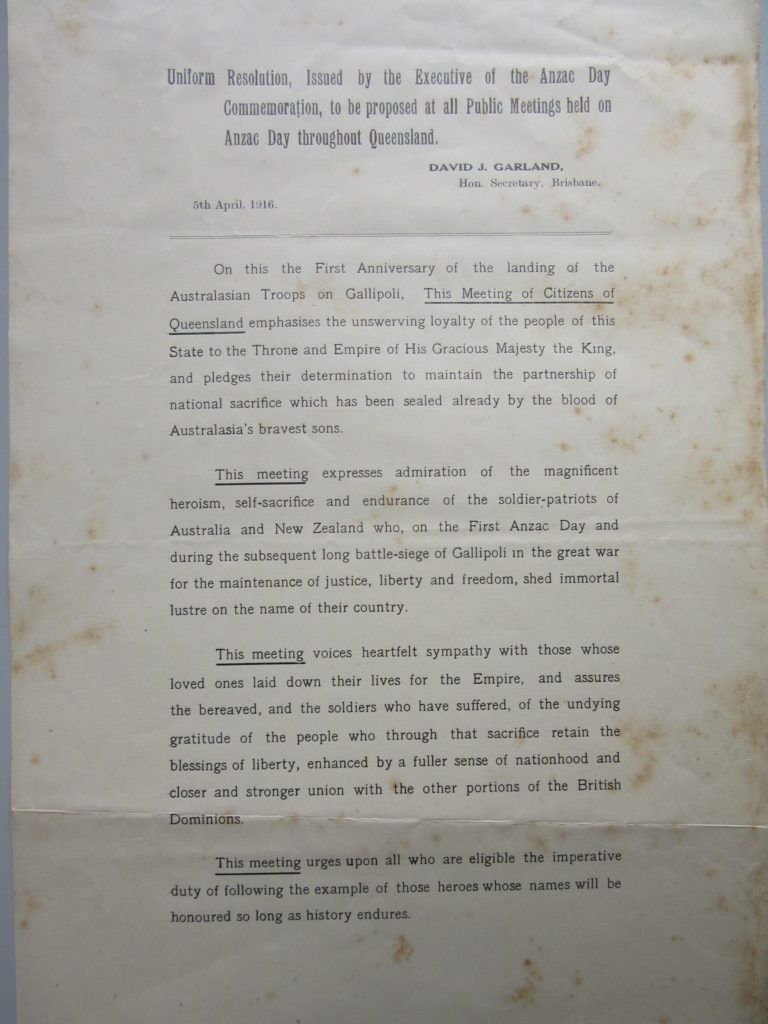

Four resolutions, expressing loyalty to the throne, admiration for the bravery of the troops, heartfelt sympathy with the bereaved, and the duties to which the State now is committed, were spoken to, and carried.

There was a notably touching interruption as the hour of nine was reached.

In common with the general cessation of all activities throughout the State at that moment the audience rose and stood in meditative silence for one minute.

The 60 secs. were fraught with significance – a silent concentration of mind upon the thought of Anzac – and as the silence grew through the ticking seconds the solemnity of the simple act deepened into something which everyone in the great audience felt poignantly.

Then Mr. Sampson broke the silence with the murmured opening notes of “The Dead March in Saul”, swelling into the glorious burst of music with which Handel expressed the Christian belief of the afterlife.

The only other incident outside the speeches was the playing of a selection of national airs, by Mr. Sampson. In conclusion the audience sang the hymn, “Abide with Me”, and the National Anthem.

The Mayor, in opening the meeting, thanked those present for their attendance, and expressed the hope that each succeeding year they would pay the honour due to their heroes. (Hear, hear.)

His Excellency the Governor, who was received with applause, recounted that on 11th of January a meeting was held in the Exhibition Hall to consider the question of commemorating Anzac Day – (Applause.) – and at that meeting certain resolutions were passed in order to bring about a fitting celebration of the day.

Since that meeting, the other States had been communicated with, and the result was that the day was being commemorated in all the Australian States, and in New Zealand, whilst His Majesty’s message had shown that a similar commemoration was taking place in England. (Applause.)

At 9 o’clock that night every centre in Queensland would be considering the objects of the day.

The first intention of those who originated the movement was to commemorate the heroic deeds of those men who 12 months ago showed that heroism and devotion to duty on the occasion of the memorable landing on the shores of Gallipoli.

The second desire was to commemorate the memory of those who died in the campaign at Gallipoli; and the third desire was the establishment of a national day for Australia, so that in the future years the generations to come might be afforded an opportunity of reasserting the objects for which Great Britain and her Allies were fighting: the objects of justice and liberty. (Applause.)

The bravery of those men who went ashore, at Gallipoli, and the heroism displayed by them, were imperishable; they would live for ages in the annals of Australia. (Applause.)

Many of the soldiers who had followed had met their death, and they too had earned the admiration and devotion of those left behind them. (Applause.)

It was his hope that in the years to come the day might be commemorated in the same spirit with which it had been commemorated in Brisbane that day.

After touching on the causes for which Britain and her Allies were fighting, His Excellency showed that the present conflict was between two kinds of thought as to how the human race later on was to lie governed, and how peace was to be kept.

That was the point that must not be lost sight of.

Australians, in celebrating Anzac Day, did not in any way depreciate what was done by their comrades, their soldiers and sailors, belonging to the homeland, as well as those sons of France who assisted on the day of the landing. (Applause.)

Anzac would ever mean the day that Australia, emerged from youth to man’s estate.

By the sacrifice of her soldiers, Australia had gained a “place amongst the nations of the world”, and her power must be felt in the counsels of the Empire in the years to come. (Applause.)

The gallantry displayed by the soldiers of Australia on the 25th April last had earned for them the admiration of the whole world. (Applause.)

They felt justified in Australia in praising the men who sacrificed their lives on Gallipoli, those who had come back to their shores, and those who would come back in the future. (Loud applause.)

Mr. Theodore said he felt deeply the honour which had been conferred upon him by the Anzac Day Committee in inviting him to address that gathering, which was a testimony to the deep feeling possessed by Queenslanders on that day of commemoration.

The great numbers of citizens who turned out in the streets that day, the large attendances at the church services and the solemnity of the commemorations throughout the State, was a magnificent testimony of the splendid work which they credited their soldiers with, who fought at Gallipoli.

Those men had won their enduring pride – they had aroused the deepest admiration of the people for they had accomplished magnificent deeds.

The men who last year left Australia’s shores, and 12 months ago landed at Anzac Cove, were pitted against the forces of Europe the forces of the oppressor. They were fighting the good fight, to uphold justice.

Australians on that day made history for Australia and, as his Excellency had said, they performed such deeds as would secure for Australia a glorious place among the nations in the world. (Applause.)

Australians hated war – they were not warlike people – but when their Empire was called upon to protect the weak, to fight against the oppressor, in the cause of justice and humanity, the overseas dominions of the Empire did not hesitate one moment in springing to arms to assist the motherland. (Applause.)

Though war was hateful to Australians, they did not stand by and see Belgium violated by the oppressor. Australia magnificently responded to the call – they sent forth their forces without any demand being made upon them.

He thought that the efforts of the Australians, wherever placed on the battle line were a credit to Australia and the Empire. (Applause.)

The Australians fought as only those could fight who were on the side of justice. They fought on Gallipoli and were tried with steel and fire and they proved their worth.

Their soldiers fought so well that every individual Australian that day felt proud of them. They had made an imperishable name for Australia in the history of the world.

Their men had set the world tingling with the story of their courage.

They were there that night to pay a simple tribute to those fallen Australians, and the feeling manifested at that gathering was only the natural feeling which possessed the minds of those who had sustained great losses.

Australia never would forget what those men, whose graves were on Gallipoli, had done for them. (Hear, hear.)

Mr. Theodore added that he desired to read a wireless message that had been received from the Premier (Hon. T.J. Ryan) [ Thomas Joseph Ryan ] by the executive of the Anzac Day Committee.

It was dated the previous day on the [ocean liner] “Philadelphia”, and was as follows: “Much regret my inability to participate personally in Anzac Day commemoration, which I hope and believe will be worthy of Queensland, and the great event, and the brave men it is designed to commemorate.” (Applause.)

Chaplain, the Rev. Dr. Merrington, who was received with great applause, moved the following resolution: “On this, the first anniversary of the landing of the Australian troops on Gallipoli, this meeting of citizens of Queensland emphasises the unswerving loyalty of the people of this State to the throne and Empire of his gracious Majesty the King, and pledges their determination to maintain the partnership of national sacrifice which has been sealed already by the blood of Australasia’s bravest sons.”

He said that that night they had expressed their allegiance to His Majesty the King and to the cause representative of their forces on land and sea, and in doing so, they recognised afresh the magnificent courage and endurance of their soldiers, known now throughout the world as ‘Anzacs’; from the landing at Gallipoli on 25th April 1915, to the evacuation towards the end of December, there was a most wonderful manifestation, of human gallantry, grit, and endurance, a spectacle of manly qualities, which, as General Birdwood said, never had been surpassed in the annals of arms. (Applause.)

Dr. Merrington read several messages from officers in high command paying tribute to the gallant work performed by Queensland troops and then recalled a number of interesting experiences which he had as chaplain of the glorious 9th Battalion.

He told his audience that the question asked of every new arrival at Anzac, including British officers who had seen service in India, was: “What do you think of the position?”

And the answer almost invariably was: “Well, I marvel how your men ever got here, and I marvel still more that you have stayed here.”

If he could transport their imagination below those high ridges, shell-pitted, and into those deep gullies, he would be enabling them to enter more fully into the inclining of the sacrifice of the gallant Anzacs.

When he landed at Anzac and went to Shrapnel Gully to the trenches to take his place with the regiment, he observed amidst the bursting shrapnel, and the constant puffs of dust that came from flying bullets, the aid bases that were sprinkled along the way.

Too much praise could not be uttered of the medical work performed in those days.

He had seen medical officers working on the wounded under fire and with shells frequently bursting overhead.

He almost immediately recognised the heroic tragedy that was taking place in connection with that spot which they afterwards came to know as Anzac.

While he was waiting at one of the traverses to rest, he observed the Church of England chaplain, the Rev. F.W. Wray DSO [ The Reverend Canon Frederick William Wray, CMG, CBE, Army Chaplain at the Boer War, Gallipoli and France ], in the middle of a track, and he heard a soldier nearby say, “I will tell you who have done blankety good work here: these blankety parsons.” (Laughter and applause.)

He next met Chaplain Gillison [ Chaplain Captain the Reverend Andrew Gillison ], who shared all the perils of those early days, and who gave the supreme sacrifice of his life for the sake of a wounded man whom he went out to rescue. (Applause.)

After he (Dr. Merrington) had taken his place with his regiment, and after experiencing several narrow escapes from bullets and shrapnel, he went down a track, and there it was he first saw Private Simpson [ Private John Simpson Kirkpatrick ] of the Medical Corps, who, with his red donkey, many times went up the bullet-swept gully, and rescued many wounded, men, and who subsequently was shot.

Men of the 9th would remember Private Simpson and his donkey. (Applause.)

Dr. Merrington paid a special tribute to the stretcher-bearers, and then to the courage, tenacity and endurance of the men in the trenches. No superlatives could he too strong for the work of those men.

Grand as were the deeds of their comrades-in-arms in the British Empire, he believed that none could have performed grander service, and none could have held on to their position better than the men who come from under the Southern Cross. (Applause.)

The resolution was carried with acclamation.

Mr. Kingsbury moved the following resolution: “This meeting expresses admiration of the magnificent heroism, self-sacrifice, and endurance of the soldier-patriots of Australia and New Zealand, who, on the first Anzac Day and during the subsequent long battle siege of Gallipoli, in the great war for the maintenance of justice, liberty, and freedom, shed immortal lustre on the name of their country.”

No words of his, he said, were needed to commend that resolution to the brain and heart of every man and woman in that vast audience.

He would say more: No human pen, no artist’s brush, and no sculptor’s chisel, would ever do justice to all that was comprised in that little word Anzac. (Applause.)

And although they were there that night to talk of Anzac, it was fitting also that they should wave the Anzac flag on other lands, on other days.

Earlier than Anzac some of their bravest fell in the islands of the Pacific. Earlier than Anzac, they lost their first war vessel, the little submarine that was caught on some coral reef.

They thought again of other lands. Men in the aeroplane service in Mesopotamia [where] two Australians lost their lives, but they knew not how.

And in the great fight between the “Emden” and the “Sydney” – they lost men too. (Applause.)

There also were Australians in Great Britain who enlisted in the home forces and on every battlefront of Europe the Australian had won exactly the same regard as they paid that night to the men of Anzac. (Applause.)

And to doctors, nurses, and the clergy – many of whom had fallen; all of whom went into the danger zone – they waved the great Anzac flag, but he would speak for one moment of others, before whom that night they bowed in reverential honour – the men who formed the first corps which left Australia on the 1st November 1914.

Of those men, 30 percent were married, and to the wives who cheered them as they went, and then wept when they were gone, they paid their deepest tribute of respect. (Applause.)

And in that corps there were some mere lads, who could not go without their parents’ consent, and here in Australia they had mothers who said, “Go, my boy, go,” and to those mothers they rendered nil sympathy that they had in their hearts, for many of them had lost their all. (Applause.)

It was just 18 months since 40 vessels convoyed the first corps leaving Australia.

They were led by the Australian battle cruiser “Australia”, and the rear was brought up by the cruiser “Sydney” and on board of those 40 vessels were 28,000 men.

After a passing tribute to General Bridges [ Sir William Throsby Bridges ], Mr. Kingsbury spoke of the sacrifices made by the Australian soldiers.

They went, he said, under a mighty impulse without having time, many or them, to weigh and measure up things that might be measured.

The speaker went on to allude to the endurance of the men at Anzac and, continuing, said that that fight had made possible Imperial federation; it had made everyone in England recognise that Australia was at last a nation. (Applause.)

The fights of a year ago were, he believed, leading to a world federation – the union of all civilised nations in one great fold – pledged to put an end to war and to set on foot a reign of ceaseless peace. (Applause.)

It had done more than that. It had purified their aims and ideals, and had taken a great amount of selfishness out of their lives.

Between £2,000,000 and £3,000,000 had been subscribed to the patriotic funds and no one holding a box on the streets of Brisbane had heard a rough word, and those who could pay had paid.

They had reached the birth of a new spirit, and the nations of the world, too, were reaching it. (Applause.)

The resolution was carried by acclamation.

Archbishop Duhig moved: “This meeting voices heartfelt sympathy with those whose loved ones laid down their lives for the Empire, and assures the bereaved, and the soldiers who have suffered, of the undying gratitude of the people who through that sacrifice retains the blessings of liberty, enhanced by a fuller sense of nationhood and closer and stronger union with the other portions of the British dominions.”

He said it was difficult to know which was the more to be admired: the courage and the endurance of the men who had performed those deeds of superlative glory at Gallipoli, or the sacrifice of the mothers who gave the men so freely to the service of their country, and for the vindication of a noble cause.

The mothers never could be repaid for their sacrifice.

Speaking of the effects of Australia’s noble response to the call of the Empire, he said Australia had had her birth and baptism in the blood of her sons, and she would have her confirmation in the highest parliament on earth, because they expected and knew that Australia would be taken in the councils of the Empire.

The resolution was carried with acclamation.

Archbishop Donaldson moved the following resolution: “This meeting urges upon all who are eligible, the imperative duty of following the example of those heroes whose names will be honoured so long as history endures.”

It does seem fitting, he said, that before they went home, someone should endeavour to put before them the great beauties to which they had all committed themselves by the commemorations that day.

Mr. Kingsbury and others had emphasised the fact that they had come to the birth of a new spirit.

He might sum up what had been said that night about those heroes of Gallipoli, what had been done for them was to set up a new standard of national character. (Applause.)

They had shown what had never been shown before: what objects were worthy, and what objects were not worthy to follow in this life.

The heroes of Anzac had set a splendid example.

What Alfred Edward Smith* [ sic ] did was typical of what their own sons from Australia did, and were ready to do. Smith was throwing a bomb, but it slipped from his hand, and fell into the trench to the imminent danger of all there.

He called a warning to his comrades and then jumped out of the trench, and climbed to a place of safety.

However, he saw that his comrades were unable to escape, and in one flash of inspiration – and surely lie must have left a vision for all time in the minds of his comrades – he jumped back into the trench, threw himself on to the bomb and was blown to pieces.

That had been the kind of thing that had been happening among their own kith and kin.

Now he came to his main theme. It was going to be in the form of a warning and an appeal.

The example of Anzac was not yet secure. It was indeed a glorious example, but if that example was to become a tradition, and that tradition was to take root in the national life, then it must fall on congenial soil.

The memory of those noble deeds must be kept alive. It was for them to see that that example took root in their national life, and blossomed in the future.

Did they appreciate the story of Alfred Edward Smith*?

All they could do was to give him the VC after he was dead, but it was their business to see that his example and examples such as his lived in their lives. (Applause.)

He reminded his hearers that there was much more treasure and blood to be spent before peace came to be signed.

Yet they read that recruiting was going down in Australia; that in Queensland there were only 10 recruits the previous day.

It was to fill the places of these dead Gallipoli heroes that the call went out for recruits and surely from Anzac Day the appeal was going to sound with greater eloquence and greater urgency than before.

It was an appeal from the graves of Australian heroes that their manly adventure, their patriotism and their sacrifice may be completed.

He was sure that the appeal was not going to fall on deaf ears; that there still was in Queensland plenty of the same manhood that first went forth.

The resolution was carried.

– from page 4 of “The Brisbane Courier” of 26 April 1916. To see a digitised version of the program that those attending this service followed, click here.

FOOTNOTE: The speaker was referring to Alfred Victor Smith (22 July 1891-23 December 1915), a 24-year-old Second Lieutenant in the 1/5th Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment of the British Army. On 23 December 1915 at Helles, Gallipoli, Smith died as a result of wounds he received in action. His Victoria Cross citation in “The London Gazette” of 3 March 1916 reads: “For most conspicuous bravery. He was in the act of throwing a grenade when it slipped from his hand and fell to the bottom of the trench close to several officers and men. He immediately shouted a warning and jumped clear to safety. He then saw that the officers and men were unable to find cover and knowing that the grenade was due to explode at any moment, he returned and flung himself upon it. He was instantly killed by the explosion. His magnificent act of self-sacrifice undoubtedly saved many lives.” This Victoria Cross story circulates in the Australian press from 6 March, some seven weeks before Anzac Day 1916.

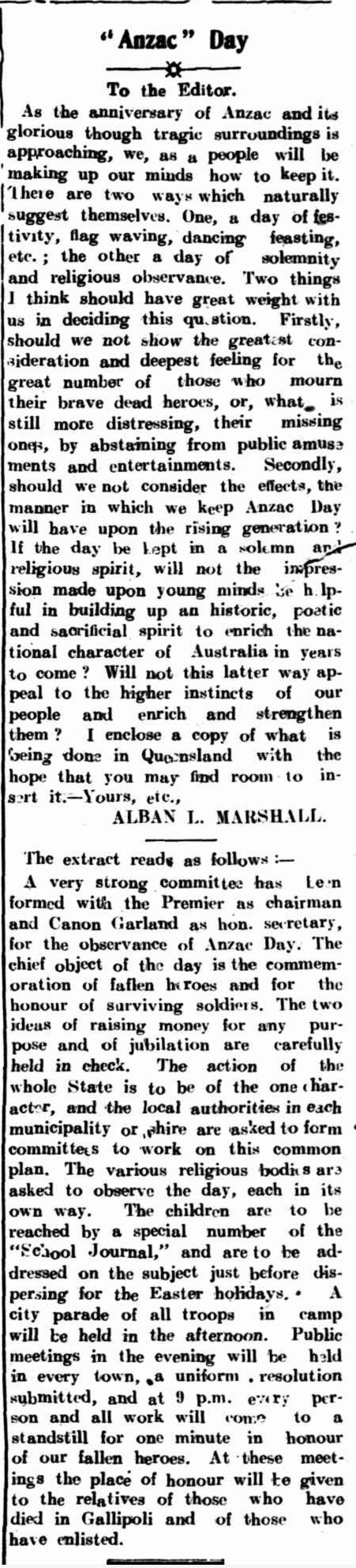

ABOVE: In “The Northam Advertiser”, in rural Western Australia, this Letter to the Editor contained an excerpt from Canon Garland’s ANZAC Day suggested format, appealing for all in the West to model their local ANZAC Day observances along the solemn lines Brisbane would be following. The item appeared on page two of the newspaper’s 22 March 1916 edition. Northam is a town located 74km north-east of Perth.