Gallipoli evacuation flag presented

ABOVE: The Padre Maxwell “Gallipoli Evacuation-Victorian Settlement Centenary Flag”, located on the western wall of Brisbane’s St John’s Cathedral, as it appeared in May 2018. This embroidery-enhanced Union Jack was presented to the Cathedral on Anzac Day 1929. Photo courtesy of Peter Collins.

ST JOHN’S Cathedral was crowded to the doors at the Anzac service held there this morning [ 25 April 1929 ].

- See also Padre Maxwell’s sermon

Many latecomers had to stand throughout the service, and others were unable to gain admittance.

Amongst those officially present were Colonel F.W.G. Annand, D.S.O. [ Frederick William Gadsby Annand ], who represented the Governor-General, his Excellency Sir John and Lady Goodwin [ Thomas Herbert John Chapman Goodwin and Lilian Isabel Goodwin, neé Ronaldson ], who were attended by Colonel Worthington-Wilmer (private secretary) [ Louis Emilius Chudleigh Worthington-Wilmer ], and the following members of his Excellency’s personal staff for Anzac Day:

- Commander E.S. Mutton, R.A.N.,

[ Edward Smith Mutton ] - Lieutenant-Colonel F.M. de Lorenzo, D.S.O. (for Brigadier-General commanding),

[ Francis Maxwell de Frazer Lorenzo ] - Colonel A.H. Marks, C.B.E., D.S.O., V.D. (Army Medical Corps),

[ Alexander Hammett Marks ] - Colonel F.A. Hughes, C.M.G. D.S.O. (artillery),

[ Francis Augustus Hughes ] - Lieutenant-Colonel D.E Evans, D.S.O. (engineers),

[ Daniel Edward Evans ] - Lieutenant-Colonel J.M. Grant, M.C. (Corps of Signals),

[ John Macdonald Grant ] - Lieutenant-Colonel J.E. Christoe (15th Battalion, the Oxley Regiment),

[ John Edward Christoe ] - Lieutenant-Colonel W. Stansfield, C.M.G., D.S.O., V.D. (Army Service Corps),

[ William Stansfield ] - Sir Charles [ sic ] Brudenell White.

[ Cyril Brudenell Bingham White ] - Alderman T. Prentice [ Thomas Prentice ] represented the Mayor (Alderman W.A. Jolly, C.M.G.) [ William Alfred Jolly ], who attended the service at Albert Street Methodist Church.

The Vice-Mayor (Alderman A. Watson) [ Archibald Watson ] also was present.

Archbishop Sharp [ Gerald Sharp ] read the eucharist, Canon D.J. Garland [ David John Garland ] read the Gospel, and Chaplain Rev. A Maxwell [ Alexander Maxwell ] delivered the address.

Dean Batty [ Francis de Witt Batty ] was amongst the clergy present.

The service commenced with the hymn,

“Brief life is here our portion,

Brief sorrow, short-lived care;

The life that knows no ending.

The tearless life is there.”

THE ADDRESS.

Rev. A. Maxwell took for his text, “Death is swallowed up in victory” (1 Cor., xv.).

They were assembled there, he said, once again to worship God, to remember with reverence and pride beloved comrades who have gone west, and to express heartfelt compassion for the many sick and wounded who still are with us.

They realised their Imperial unity today in that solemn act of united worship.

Though sundered far, the various portions of this world-wide Empire are united today in one communion and fellowship, in tenderest sympathy for the sorrowing and in prayer and thanksgiving for the heroic immortal dead, and for the great final victory.

Serving himself as a chaplain in that great campaign, and being also represented by his two sons, a son-in-law and brother, he had a fellow feeling for those who suffered.

In the Gallipoli campaign over 5,000 sick and wounded passed through the hospital ship of which he was the only chaplain.

The first thing that shone out in all that he had seen in those soul-stirring experiences, was the love of the Digger for his “cobbers”, which was something most beautiful to see.

The next thing was the wonderful attention of the nurses and doctors to their patients, and the unbounded gratitude of the men, and the marvellous generosity of the Red Cross Society in supplying comforts.

The men showed splendid courage when wounded, even when in sore pain or when dying, which made one feel proud to belong to such a race. It was a privilege to minister to such manly men.

All the world said the task which the Anzacs faced was an impossible one, and so it was to all but such men as Australia mourns today, the bravest and best of her sons.

A British general said to him, “If they had all been like these Anzac men we should have got through to Constantinople long ago.”

“What kind of courage was theirs who dared to do and to die so heroically?

“We do not claim for these men who were our comrades,” said the ex-padre, “that they were saints, any more than we claim this for ourselves.

“What we do claim is that they were men of whom any country might be proud because, in the hour of fiery trial, they counted not the cost, but did their duty.

“They are men of whom not only Australia and New Zealand are proud, but whom the whole world has enshrined in loving memory as some of the world’s heroes in the greatest war in history.”

April 25, 1915, said the speaker, was a great day for Australia.

“Honour was done to her that day by our brave lads which would inspire not only the present generation but also generations unborn.

“All the Anzacs were not dead. Thousands were happily still with us.

“Best of all, the Anzac spirit was not dead. That dauntless spirit was a rich heritage which would inspire this young nation for all time.”

He had seen the faces of the children in the State schools light up with honest pride at the mention of Anzac.

It was a happy coincidence that the Anzac commemoration took place in the Easter season, when the thought of life immortal was uppermost in Christian people’s minds.

It was impossible to think of those brave men who laid down their lives for God, for their country, for honour and for freedom as being dead.

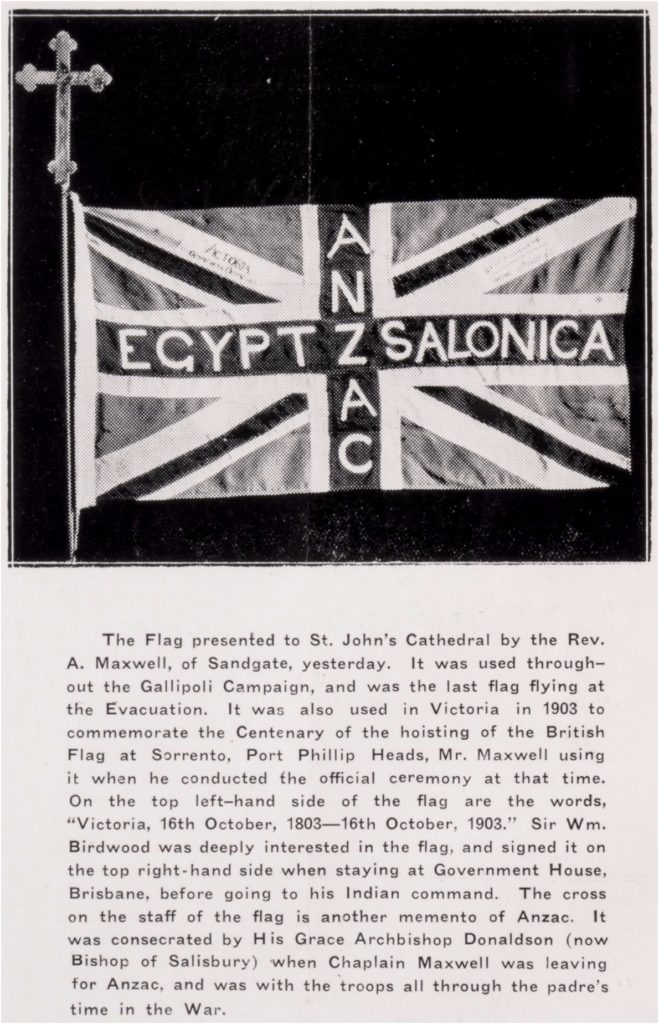

ABOVE: How Brisbane’s “The Telegraph” newspaper covered the arrival of Padre Maxwell’s Gallipoli Evacuation Flag in its 26 April 1929 editions.

Concluding his address, the ex-padre exhibited a small Union Jack which he said was used in the celebrations of the centenary of Victoria.

This flag he took with him to Gallipoli, and it was the last British flag which flew there.

General Sir Thomas [ sic ] Birdwood [ William Riddell Birdwood ] had written his name on a corner of the flag.

The speaker also held up a cross which Archbishop Donaldson [ St Clair George Alfred Donaldson ] had dedicated, and which he had used throughout his ministrations as a padre. These he presented to the Cathedral.

Mr. George Sampson, F.R.C.O., presided at the organ.

— from page 2 of “The Telegraph” (Brisbane) of Anzac Day, 25 April 1929.