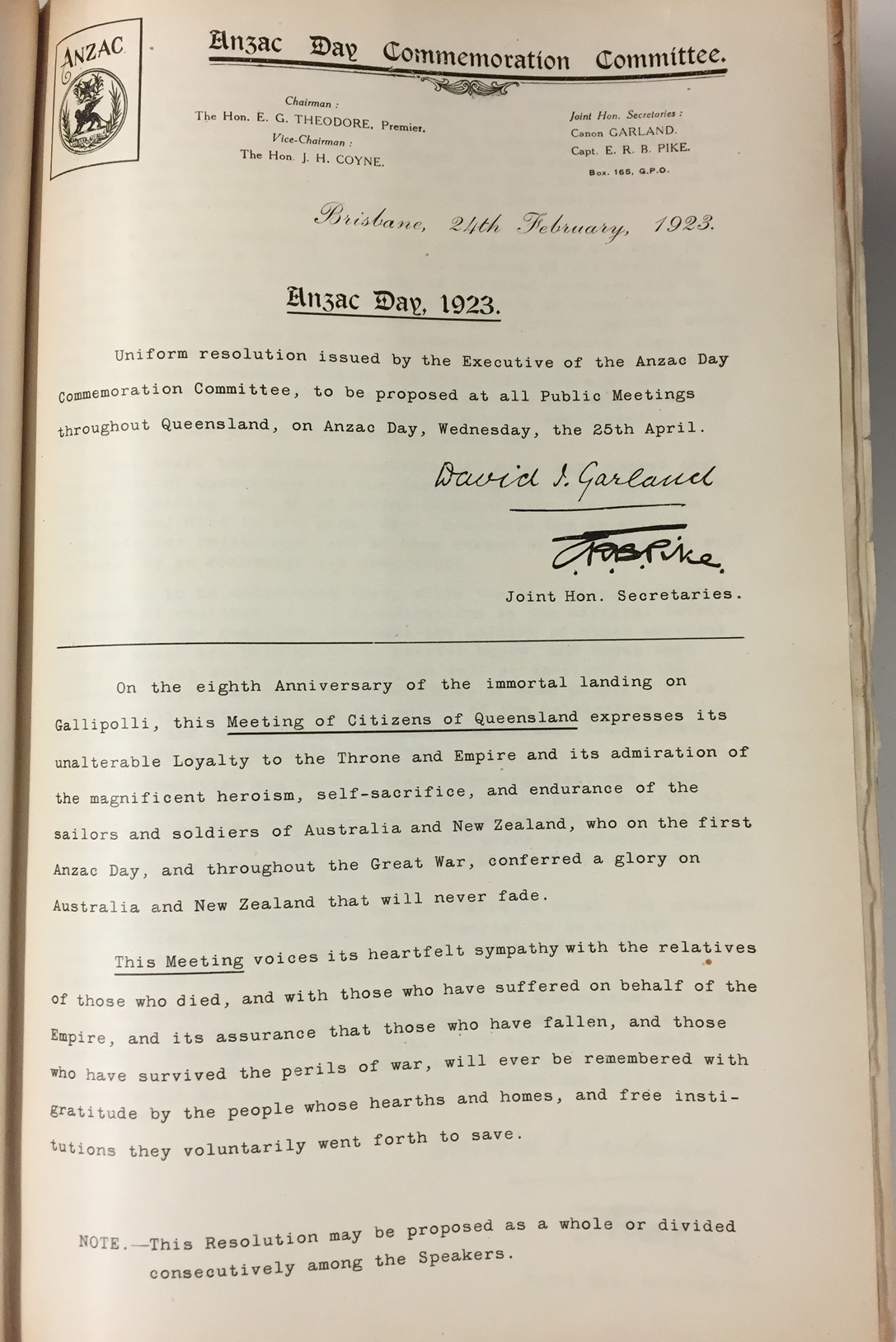

ABOVE: The instructions for the observance of Anzac Day as issued by the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee (Queensland) on 24 February 1923. From the ADCC Minute Books in the State Library of Queensland Collection.

HEROISM AND SACRIFICE.

LOVE AND ENDURANCE.

THE ANZAC IDEALS.

TYPIFIED IN THE UNION JACK.

“If the ideals for which these men fought and died so nobly are to be perpetuated,” said Canon Garland [ David John Garland ] in the course of a stirring address in the Exhibition Hall last night [ 25 April 1923 ], “they must be implanted in the children of today, and to do that we must tell them the mettle of their fathers and brothers.

“There is the same mettle present in the blood which flows through their veins, and it only needs an inspiration to bring it forth.

“Then the next generation will have the same ideals of heroism, love, sacrifice, and endurance which the flag of England — the Union Jack — typifies to us.”

A GREAT GATHERING

The eighth anniversary of the landing of the Australians at Anzac Cove was fittingly commemorated last evening, when, with pride, and tinged with sadness, an audience of some 3,000 citizens crowded the Exhibition Hall to honour the memory of Australia’s noble dead.

Every nook and corner of the great concert hall was filled, and among the audience were a large number of returned nurses, invalids from, military hostels, and incapacitated men, while in the choir galleries were some 200 Boy Scouts in uniform.

His Excellency the Governor (Sir Matthew Nathan) [ Matthew Nathan ] took his seat on the dais shortly after 8 o’clock.

He was accompanied by Sir Alfred Pickford (Commissioner for Oversea Scouts and Immigration) and the Mayor of Brisbane (Alderman H.J. Diddams) [ Henry John Charles Diddams ] and attended by Captain Hammond [ Henry Armstrong Hammond ].

Others present included His Grace the Archbishop of Brisbane (Dr Sharp) [ Gerald Sharp ], Rev. Dr Bickersteth (Canon of Canterbury Cathedral, and Chaplain to His Majesty the King) [ Kenneth Julian Faithful Bickersteth ] and Mrs Bickersteth, Chaplain-Major Lynch [ Paul Lynch ] (representing His Grace Archbishop Duhig) [ James Vincent Duhig ], Canon D.J Garland, V.D., and Mrs Garland, Major-General J.H. Bruche [ Julius Henry Bruche ], Lieut-Col. W. Stansfield, C.M.G., D.S.O., V.D. [ William Stansfield ], and Mrs Stansfield [ Amy Louisa Huxham, neé Rogers ], the District Naval Officer (Commander Mutton) [ Edward Smith Mutton ], and Acting Premier (Mr J. Huxham) [ John Saunders Huxham ].

“THE LIVING AND THE DEAD.”

The Chairman (Alderman Diddams) said that, once again, for the eighth time, they were met to commemorate the entrance of the Australian and New Zealand forces into the grim arena of the Great War and to record again their love and gratitude to all those who had fought and served, and especially those who had suffered, bled and died in order that Australia would live and remain free, and that the British Empire throughout the world should continue to exist.

Sixty thousand of them had given up then lives in order that Australia and the Empire should continue to exist.

That night they again thanked them all — the living and the dead.

They thanked the brave women of the community who, with breaking hearts, had given up their husbands, their sons, their brothers, and their lovers for home and country.

They thanked the patient nurses, who, at home and abroad, so tenderly soothed and relieved the wounded and stricken men, also the army of Red Cross workers, who, for nearly four Iong years, devoted their energies without cessation for the comfort of our soldiers. Above all that night, they held in reverence their heroic dead:

Peace! Peace! They are not dead, they do not sleep.

They have awakened from the dream of life…

They have out soared the shadow of our night, Envy and calumny, and hate and pain

And that unrest which men miscall delight, Can touch them not in torture not again.

From the contagion of the world’s slow stain: They are secure, and now can never mourn,

A head grown grey, a heart grown cold in vain.

As they, in common with united Australia, remembered our soldiers that night — the living as well as the dead — and what they had done for us, too all succeeding generations of Australians would remember the greatness of then achievement. (Applause.)

THE NINTH BATTALION.

His Excellency recounted the events of the historic April 25.

When he was a boy, he said, he had read many times “A Voice From Waterloo” — an account of the fight by one who had fought there as a non-commissioned officer.

Every year before April 25 he read of the landings at Gallipoli, and thought of the dogged attack on that day in 1915 as a companion picture to the one of the resolute defence of 100 years before.

The centre of the picture was to him always then Queensland battalion, the 9th, which was to be on the right of the line in the 3rd Brigade, told off to cover the landing of the Australian and New Zealand troops.

Of the 9th Battalion there remained 442 men out of some 960 that had gone into action.

More than half had been killed or wounded or were missing, and afterwards it was found that all the missing were killed or wounded, for in those days, only one man of the First Australian Division was taken prisoner by the Turks.

The loss in officers had been particularly heavy.

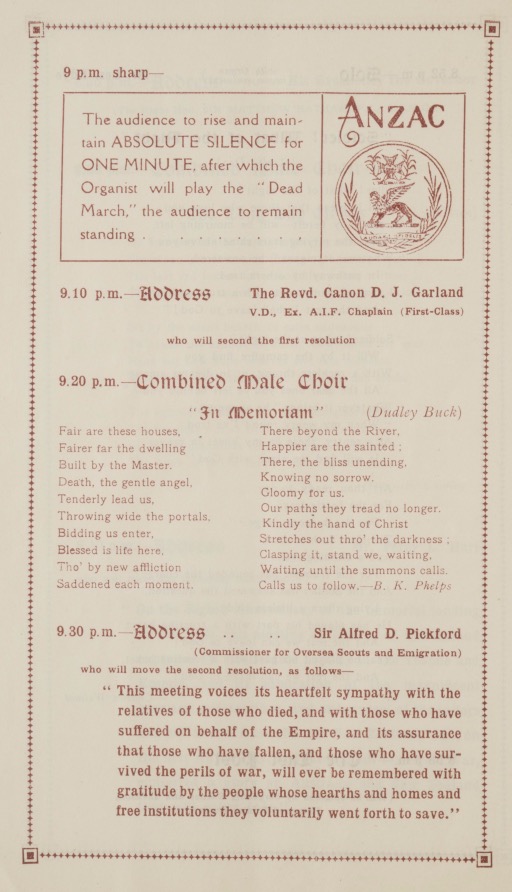

ABOVE: The inside page of the Order of Service booklet issued by the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee (Queensland) for the eight o’clock civic observance in the Exhibition Building (now the Old Queensland Museum Building on Bowen Bridge Road, Bowen Hills, Brisbane, on Wednesday, 25 April 1923. From the ADCC Minute Books in the State Library of Queensland Collection.

They had given such direction as they could to a fight which, from its nature, admitted of but little. All ranks had fought with happy courage, seemingly careless of the death and dismemberment going on around them, of fatigue and discomfort so great as to have been pain.

Such names as: Boase, A.J.B.; Costin, J.W.; Fortescue, C.; Harman, H.; Harrison, P.W.; Haymen, F.G.; Milne, J.; Robertson, S.B.; Robertson, J.C.; Ryder, J.F.; Salisbury, A.G.; Thomas, G.; and the doctor — Graham Butler — must never be forgotten in this land, and he hoped that if there was not already a history of the work of the 9th Battalion at Anzac one would be prepared to preserve in a form in which boys could read the story of the deeds of the Queenslanders who fell fighting there, and of those who, happily for them, still gloriously heightened the value of the people of this country.

“There is no story of the Empire more worth while the telling,” concluded His Excellency.

THE FIRST RESOLUTION.

Mr Percy L. Hart moved:— “On the eighth anniversary of the immortal landing on Gallipoli, this meeting of citizens of Queensland expresses its unalterable loyalty to the Throne and Empire, and its admiration of the magnificent heroism, self-sacrifice and endurance of the sailors and soldiers of Australia and New Zealand who, on the first Anzac Day, and throughout the Great War, conferred a glory on Australia and New Zealand that will never fade.”

Mr Hart said that 60,000 men had left Australian shores.

Thirty-four thousand had returned, and the larger proportion of them had found employment.

Their enemies would think that they spoke with tongue in cheek unless they took steps to see that none was out of work.

There were a thousand beggars that night on the books of the Returned Soldiers’ League who were seeking, not charity, but honest work.

Some of the boys were wayward sometimes, but when people remembered their sacrifices in the firing zone, and the days of hunger and nights of cold, they would excuse what might seem inexcusable weakness.

AN IMPRESSIVE INTERLUDE.

At 8:58pm the huge gathering, at the instance of the chairman, rose in silence, with bowed heads, while Sergeants Barnes and Jackson, returned soldier buglers, sounded “The Last Post”.

The impressiveness of the scene was added to considerably when, after a moment’s absolute silence on the part of the audience, the grand organ, responding to the touch of the city organist (Mr Geo Sampson, F.R.C.O.), pealed forth majestically the sad strains of Handel’s “Dead March in Saul”.

Many of those in the audience could not restrain their emotion, and in the galleries more than one war widow were quietly sobbing.

THE SPIRIT OF SACRIFICE.

Canon Garland seconded the first resolution in an eloquent address, which was punctuated with the applause of the audience.

He told a touching story of the self-sacrifice of the noble men of Anzac, how they had shared their scanty rations with the starving victims of the enemy’s retreat, and how, on one occasion, when the Turks had been smitten with typhoid, they had been presented with supplies of condensed milk from their enemy — the Australian soldier.

He expressed the hope that so long as the name Anzac should be spoken in the English tongue, its memory would be perpetuated in the way it had been perpetuated during the last eight years.

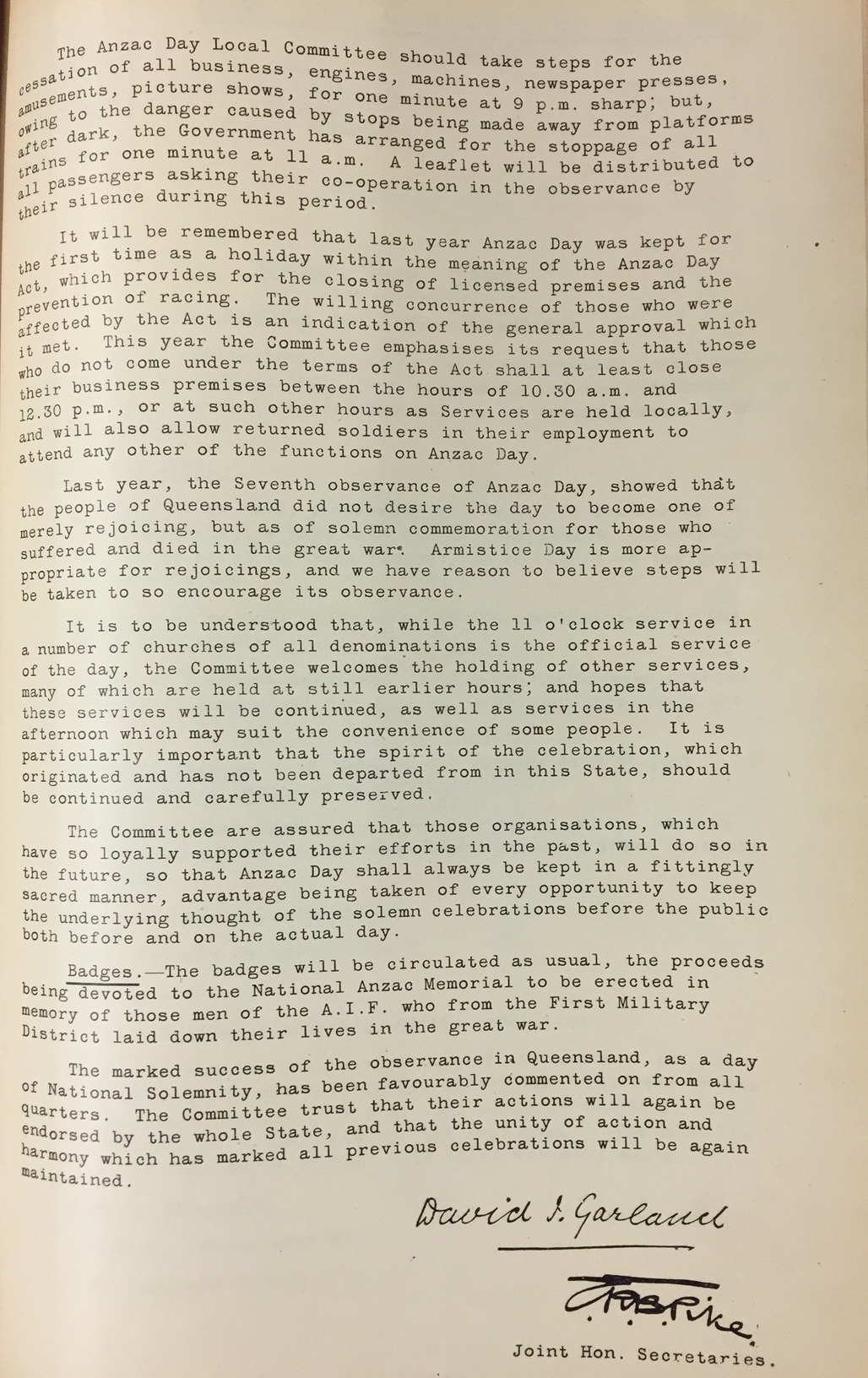

ABOVE: The detailed instructions for the observance of Anzac Day as issued by the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee (Queensland) on 24 February 1923. From the ADCC Minute Books in the State Library of Queensland Collection.

He wished to publicly refer to the splendid action of the State School teachers in regard to the observance of Anzac Day.

There had not been one school in the metropolitan area where the teachers had not taken great pains to prepare the children for the observance of Anzac Day, and they also had gone to the trouble of arranging special addresses on what Anzac Day meant to all all true Australians.

“If the ideals for which these men fought and died so nobly are to be perpetuated,” said the speaker, “they must be implanted in the children of today, and to do that we must tell them the mettle of their fathers and brothers.

“There is the same mettle present in the blood which flows through their veins, and it only needs an inspiration to bring it forth.

“Then the next generation will have the same ideals of heroism, love, sacrifice, and endurance, which the flag of England — the Union Jack — typifies to us.”

THE SECOND RESOLUTION.

Sir Alfred Pickford moved: “This meeting voices its heartfelt sympathy with the relatives of those who died, and with those who have suffered on behalf of the Empire, and its assurance that those who have fallen, and those who have survived the perils of war, will ever be remembered with gratitude by the people whose hearths and homes and free institutions they voluntarily went forth to save.”

A perpetuation of the memory of the men of Anzac, he said, could be best secured for the coming generation by the care they took and the effort they made today in this direction, so that those who came after could take up the torch which many of those who fought could never carry again.

In that way the memory of these splendid heroes would be kept green.

Lieut.-Colonel W. Stansfield seconded the resolution, and gave intimate personal touches of the life of the Australians at the Front; the eagerness of the Light Horsemen to get into the thick of things, and, above all, their cheerfulness and self-sacrifice in the face of danger.

At intervals a combined male choir, comprising members of the Brisbane Apollo Club and the Blackstone-Ipswich Cambrian Choir, under the conductorship of Mr. Leonard Francis, rendered “The Long Day Closes” (Sullivan) in “In Memoriam” (Dudley Buck).

Mr. Les Edye (a member of the famous 9th) gave Airlie Dix’s “Soldier, What of the Night”, while a fine histrionic effort by Mr Harry Borradale — Henry V’s stirring speech before the Battle of Agincourt (Shakespeare) — was greeted with loud applause.

“Abide With Me”, sung with intense feeling by the large audience, and the National Anthem brought a memorable meeting to a conclusion.

— from page 7 of “The Brisbane Courier” of 26 April 1923.

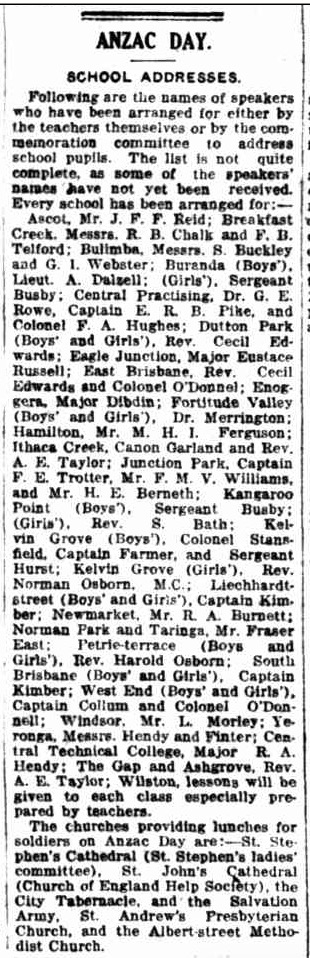

ABOVE: The list of speakers allocated to address school assemblies across Brisbane on Anzac Day 1923. From page 4 of “The Daily Standard” of 24 April 1923.