ANZAC Day address

ABOVE: This image appeared on page 37 of the Anzac Day Commemorative Committee of Queensland’s 130-page publication, “Anzac Commemoration 1921: A Brief History of the Movement. Sermons and Addresses delivered throughout Queensland; The Immortal Story of the Landing”, compiled by Harry John Charles Diddams, in October 1921. Included in the publication is the address Canon Garland delivered in Brisbane’s Toowong Cemetery on Anzac Day 1921. He is pictured here among the freshly-dug graves of veterans who saw active duty in the Great War, bracketed by the kinfolk of those Diggers.

THE REV. CANON GARLAND, V.D.

Hon. Secretary.

Anzac Day Commemoration.

“Their name liveth for evermore.” (Ecclesiasticus, chapter 44, verse 14).

IN each of the battlefield cemeteries in which lie at rest the bodies of those Soldiers of the Empire who laid down their lives for us there is erected as the sole monument a tall cross, visible for miles around, and at its foot an altar in stone.

The monument, in its noble dignity proclaiming the great Sacrifice of Calvary, unites thereto the sacrifice of those who also laid down their lives for their friends.

No words could have been more aptly chosen for its solitary inscription no less dignified than the monument itself:–

“Their name liveth for evermore.”

It is a matter of congratulation that the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee – the body which originated and has been for the last five years responsible for the observance of Anzac Day in Queensland and, indeed, for creating its observance throughout the Empire – should have chosen these words this year as the motto for Anzac Day.

It is to be hoped they will ever so remain.

In themselves they are complete, and are all the more dignified and suitable because there is an absence, not merely of jubilation, but also of anything approaching self-adulation.

The words direct our attention away from ourselves, our own doings, and exclusively to those who, for our sakes, loving not their lives even unto death, we call dead, but who, indeed, are alive unto God, because “God is not the God of the dead, but of the living, for all live unto Him.”

Their name, written in the Lamb’s Book of Life, liveth for evermore before God.

There are some of whose heroic deaths we know, the stories of whose self-sacrifice and heroism will be handed down from generation to generation and in days to follow, when Australia has millions upon millions of people, their names will still “live for evermore” as the first fruits of bravery in the annals of the beginning of her history in the nations of the world.

In addition to those whose heroic tales are known, there are those who died equally heroic deaths, though no pen has recorded their glory.

In the hearts of those who loved them – who are bereaved and still today mourn and grieve, their names indeed are deeply engraved – to these mourners we today offer the homage and sympathy of our hearts, assuring them that it is no sense of victory or rejoicing at our own deliverance on for us by those who died which brings us together today, but grateful reverence for the dead and for those who still mourn them.

Though the hearts of the mourners will pass from this world, yet of those who laid down their lives for us it shall be said by the generations who come after us so long as tongue can speak, “Their name liveth for evermore.”

Yes, and somewhere more than even in the long annals of human history in the Lamb’s Book of Life, in the presence of God Himself, “their name liveth for evermore.”

As in Scripture the use of the word “name” signifies the person referred to, so it means not merely their memory but that they themselves live for evermore, and so to mourners the Christian faith brings this comfort – and Anzac Day would emphasise its lesson they are not dead, they live for evermore, and by that faith the assurance also that we shall see them again and know them and hold converse with them, which shall be sweet because without the taint of sin.

And because they are not dead we follow them with our prayers into the life beyond, as we followed them o’er land and sea.

We gather together on Anzac Day to plead collectively for them that sacrifice on Calvary to which they united themselves by offering themselves a living sacrifice after the example of Him who, by word and from the pulpit of the Cross, taught us that “Greater love hath no man that this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

As this thought brings us comfort, it brings us solemnity also – not the sorrow of those without hope for them that sleep in Him, nor the swamping of our grief in noisy demonstration, but the emphasising in mind and thought of the reality of the future life.

The cause of all these 60,000 deaths of our boys must not be forgotten.

It was never the will of God that these, the best of our young men, the flower of our people, should in the prime of life be cut off, and cut off amidst all the horrors of war.

God sent them into this world to live the lives of full manhood, to be the fathers of souls created for His glory, to inhabit Heaven for all eternity.

It was neither God nor His will that cut them off in their beauty and strength – it was sin.

We need not be particular now to say it was all the fault of Germany, though forever Germany and the teaching which drove Germany to her sin will remain a dark page in the history of our race.

It was the sin of the whole Christian Church failing to convert the world – failing to inspire men with the true teachings of Jesus Christ.

Wherever the blame lies, and however it is apportioned, it was sin, our sin, which brought about the war and all these deaths against the will of God.

As thus we think of sin being the real cause of their deaths, again there is no room for anything but a solemn observance of Anzac Day – the All Souls’ Day of Australia – and, therefore, we come before God, not in the bright vestments of festival and the joyous music of triumph, but with all the tokens of Christian penitence and sorrow.

“Their name liveth for evermore.”

As their name liveth for evermore before God, so, too, as long as our hearts shall beat in human fresh their memory will be as fragrant as the incense in the Temple of God; fragrant, because in spite of all their human faults – which, we pray God to pardon and to wash away in the blood of the Immaculate Lamb – there was a beauty which already has begun to overshadow their heroism.

They were brave and loved not their lives unto death, but they were more than brave – audax at fıdelis – faithful to their ideals, faithful to us for whom they died, faithful to one another.

Of those ideals and how they maintained them time would fail to tell.

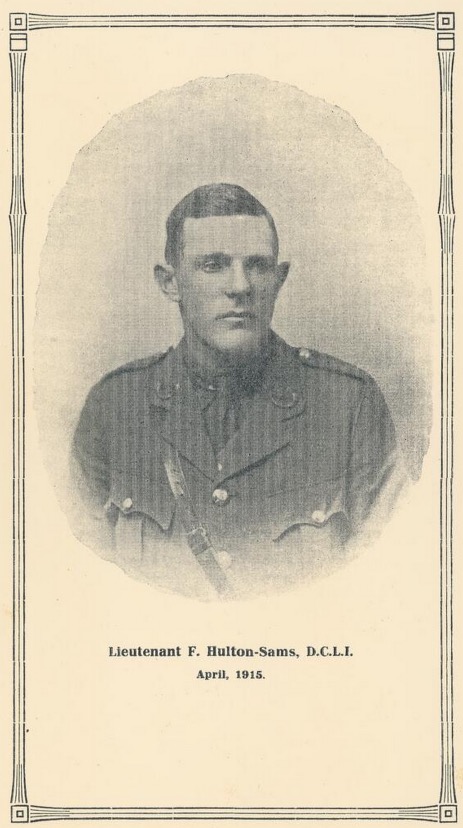

Who can ever forget the story of Hulton-Sams [ Frederick Edward Barwick Hulton-Sams ], especially those from Queensland’s west, who looked upon him as their ideal of religion:

Moreover as God’s priest he stood –

Preached in rude camps Thy message free,

Gave of Thy Body and Thy Blood

Into rough hands held out for Thee.

And the ideal of the highest sacrifice which he thus proclaimed in administering Holy Communion he fulfilled in his own death.

The men with whom he had shared the fighting lay wounded out in No Man’s Land. They were dying and craving for water.

He brought them water; he had to crawl on his face to do so, and, taking to them the cup of cold water in Christ’s name, like Him, whose priest and soldier he was, he was wounded in the side and died.

It was not only he from whom as a priest one would expect the exhibition of these ideals, the ordinary Australian soldier was equally ready to sacrifice himself, not only for his comrades, but also for those who had no claim upon him.

When capturing Damascus our Australian boys found the hospital in an unspeakable condition.

They at once proclaimed that their scanty ration of tinned milk should be given to the hospital, in which lay dying not only some of their comrades, but many of the enemy.

Later on as they continued that most marvellous cavalry march, and rode over Syria, where thousands of the natives had died, starved to death by the Turk and German, they found surviving natives, literally living skeletons, skin and bone.

Our own Australian boys, short of food themselves, because it could not be brought up quickly enough to keep pace with the rapidity of their movements, went hungrier, and shared their own scanty rations with the starving women and children of Syria.

I have seen the tenderness with which they nursed and tended some little deserted child whose language they could not speak, and who could understand nothing of these long, lean-looking Australians, but that they were full of kindness and tenderness.

No wonder that the Patriarch of Antioch and Damascus wrote to his fellow-Syrians in Sydney telling them that when the Australian soldiers came home the Syrians were to be good to them, because they were so kind and gentle.

Thus, indeed, “their name liveth for evermore” in the hearts of those to whom they showed this depth of Christian charity, brave to the last degree, yet faithful to their ideals.

Their name liveth for evermore kindness and gentleness.

I remember, too, in the Jordan Valley here so many of our Queensland boys, as well as other Australians, lived under the most trying conditions long weary months, when I spoke to those who seemed to me really ill, and urged them to go down the line to hospital; they refused, because they stated they could not desert their mates.

I thought of that unselfishness which, to me, stood out more vividly than to them, because I had not long before been in the streets of the capital cities of Australia, where I had seen men sturdy in health leaning against verandah posts as they waited for trams to racecourses.

There would have been fewer deaths in the aggregate had those who hung back shown the same spirit of sacrifice as those whose name liveth for evermore.

As we think of that additional sacrifice of life made necessary by the selfishness of some, Anzac Day should be kept solemnly and seriously.

I blame not only those who refused to go, but even more the whole body of Christian influence which was so weak and feeble that it had not built up the true ideals of sacrifice and duty, and thus again we see that the restrained and chastened spirit of penitence and Christian sorrows and not of rejoicing should occupy our thoughts on Anzac Day.

“Their name liveth for evermore.”

Is that to be idle boast and mere talk, the erection of statues symbolic of no ideal, or is it to mean to us the maintenance of those ideals which they fulfilled.

Are we to be worthy of them – of the same mettle?

“Their name liveth for evermore”, not for their bravery only, not for deeds of heroism merely, but also and more because of kindness and gentleness which shall never fade from the memory and heart of enemy and friend alike, and never from the memory and the heart of Australia so long as we prove worthy of them and their sacrifice for us.

– from pages 37 to 41 of the Anzac Day Commemorative Committee of Queensland’s 130-page publication, “Anzac Commemoration 1921: A Brief History of the Movement. Sermons and Addresses delivered throughout Queensland; The Immortal Story of the Landing”, compiled by Harry John Charles Diddams, in October 1921. The address above was delivered by Canon Garland amid the gravesites of former Diggers of the Great War at Brisbane’ Toowong Cemetery, on Anzac Day, 1921.

FOOTNOTE: Below is an excerpt from the book, “Frederick Hulton-Sams, the Fighting Parson: Impressions of his Five Years’ Ministry in the Queensland Bush, Recorded by Some Who Knew and Loved Him” (also titled, “Frederick Hulton-Sams, Priest, Athlete, Patriot”), published at Longreach, Queensland, by Theo. F. Barker, in 1915. The section is titled “Extract from a private letter dated 2nd August, 1915”:–

“He died a glorious death, that is a British officer and a gentleman – commanding a company in an important position, and above all, sticking it where others might have failed.

“The circumstances were these.

“We were hauled out of our billets at 2 a.m. on the 30th, and had to hurry up in fighting order to where another Brigade had been driven out of their trenches with liquid fire.

“We had to go up to a part in a counter-attack.

“The counter-attack ended at the edge of a wood called Zouvave Wood.

“C Company was left with your brother [ Frederick Edward Barwick Hulton-Sams ] in command, all other officers being killed or wounded.

“We were hanging on to the edge of this wood for all we were fit, and the Germans were trying to shell us out of it.

“C Company were splendid. We all knew they would be, for they would d anything for your brother.

“All the afternoon of the 30th they were there, and all night.

“That night the Germans attacked us again, bombs and liquid fire.

“C Company still stuck to it and through that terrific shelling they never flinched, although they lost heavily.

“They were there at 10 a.m., and I crawled to and talked to your brother several times. He was magnificent and cheerful.

“His last words to me before he was hit were ‘Well, old boy, this a bit thick, but we’ll see it through, never fear.’

“I left him then to go somewhere else, and I didn’t see him again.

“His Company Sergeant (a man called Fuller) told me that about 10 a.m. your brother crawled away to see if he could get any water for the men – many of whom were wounded and very thirsty.

“He was hit by a piece of shell in the thigh and side, and killed instantly – or at any rate never regained consciousness.

“He can have suffered no pain, and he died doing a thing which makes us feel proud to have known him.

“He was a fine officer, a fine friend, and worshipped by his men.

“That is all I can tell you about him. We were relieved the night following, and we got his body and buried at the graveyard in the rear of the fighting line at Hooge.”

ABOVE: The Reverend Frederick Edward Barwick Hulton-Sams, known throughout Western Queensland as “The Fighting Parson”. This image appeared in Theo. F. Barker’s book, “Frederick Hulton-Sams, the Fighting Parson: Impressions of his Five Years’ Ministry in the Queensland Bush, Recorded by Some Who Knew and Loved Him” (also titled, “Frederick Hulton-Sams, Priest, Athlete, Patriot”), published at Longreach, Queensland, in 1915. The proceeds from the sale of the book were to be “devoted to the payment of the cost of building Jundah Anglican Church which will be dedicated to the memory of Reverend Frederick Hulton-Sams.” Lieutenant Frederick Edward Barwick Hulton-Sams, 33, served with the British Army’s Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and was killed in action on 30 July 1915 near Hooge, Belgium, and has a memorial in the Sanctuary Wood Cemetery, five kilometres east of Ieper town centre, on the Canadalaan, a road leading from the Meenseweg.